Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust has just opened at the Royal Academy. It’s a show no graphic designer should miss.

Cornell occupies an ambiguous position in the art world. I sense that critics and historians find him hard to place. While flirting with recognised movements from symbolism to surrealism to modernism but completely untrained as an artist, Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) made highly eclectic work that bends conventional artistic categories and genres. Designers, on the other hand, may find him to be much more mainstream.

To understand why is to know something of his background and his way of working. Cornell’s life spanned much of the 20th century, but despite an interest in far-off places he barely left his home state of New York. From an early age he cared for his widowed mother and his disabled brother, an experience that perhaps helped confine his work to a personal interiority, although ‘confining’ is hardly the right description of his creative explorations. The work on show in this exhibition demonstrates his own creation of a virtual world long before the age of the internet.

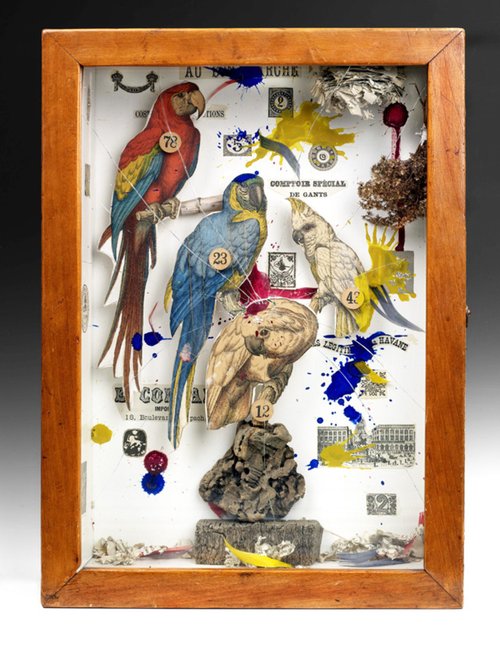

He was an assiduous gatherer, collector and hoarder of ephemera and objects. With careful selection and precise placement he put together collages and cabinets of curiosity, fantasy and narrative. By recycling imagery from ‘foreign’ places – things such as postage stamps, maps, old engravings and photographs – into compositions defined by frames or containers, his work moves through time and space while standing still. His free associative use of found imagery to create a new whole is a technique familiar to many designers, for whom selection and placement are part and parcel of making a design work.

Cornell used text and typography too as part of his work, deploying the components with a highly developed aesthetic sensibility. Sitting in his suburban New York studio at 3708 Utopia Parkway, poring through his files and boxes, Cornell reminds me of today’s designer who now finds herself searching Google for the right visual references and often making connections by coincidence or random surfing. Of course, Cornell’s library and archive was painstakingly acquired over time from the secondhand stores, bookshops and museums he visited in New York. The worlds he constructed are at different times romantic, nostalgic, quaint and sinister. Like a Victorian traveller, naturalist or collector he draws in everything he can find to populate his interior voyage of discovery. Sometimes his vision becomes obsessive and dark, both literally and metaphorically. He dedicated some of his works to ballerinas and Hollywood movie stars, reflecting his virtual passions and his entrancement with all things theatrical. Memories and mysteries loom large in Cornell’s world.

During his lifetime he maintained a dialogue with a number of artists from Marcel Duchamp to Andy Warhol and exhibited alongside contemporaries such as Robert Rauschenberg, all of whom would have recognised Cornell’s unique talent, and it is clear to see the all too obvious debt that artists such as Peter Blake and Damien Hirst owe to Cornell, as well as the ongoing influence he exerts on contemporary installation and performance artforms.